Yesterday was rough, as you may already know. But I’ll show you anyway just in case:

That’s what a 5% intra-day loss in the Nasdaq looks like. It’s really ugly, especially for such a major index. In fact, there have only been 45 uglier days since 1985:

Yet we saw a thrilling rally in the index just the day before, giving little indication of the nosedive to come. Now we’re all practically sore from whiplash – and just a tad curious as to what the $%#@! is going on. So, on that note:

What the $%#@! is going on??

In short, a lot. But that’s always the case, so let’s just outline a few probable factors – and rule out some that don’t fit.

First, the good news

On Wednesday, the Fed announced a rate increase of 0.5%. Such news isn’t typically met with enthusiasm in the markets… but the Fed also announced that rates will not be increased by 0.75%. And it seems traders were downright jubilant in their relief at hearing that.

But several inconvenient truths remain stubbornly in place despite the Fed’s clemency, and I suspect the recollection of those truths caused some investors to sober up quickly. Once they did, a structural quirk of the market led more and more to rapidly follow suit, causing the would-be sobriety to spiral into something like panic.

Let’s take a quick look at both pieces of the puzzle:

The bad news (that isn’t really news)

Here’s the thing: markets have already been touchy all year, thanks to various economic obstacles and political upheavals. Chief among these is a triple-whammy of increased costs for firms:

- Skyrocketing wages due to an apparent labor shortage

- Skyrocketing material costs due to ongoing supply chain snarls

- Imminent interest rate increases, which especially impact companies – like tech-based Nasdaq leaders – that rely heavily on debt financing.

Although these are significant pressures, investors may not respond to them as quickly or dramatically as they do to headlines like a Fed announcement or SCOTUS leak. But they will respond eventually – and just a few doing so may be enough to set off a chain reaction.

The sell-off snowball effect

Nowadays, a significant number of daily trades happen through mutual funds and ETFs rather than individual company stocks. So when investors want to “risk off,” they’re not necessarily choosing to sell Apple or Amazon or Microsoft. Rather, they end up selling a bunch of stocks indiscriminately.

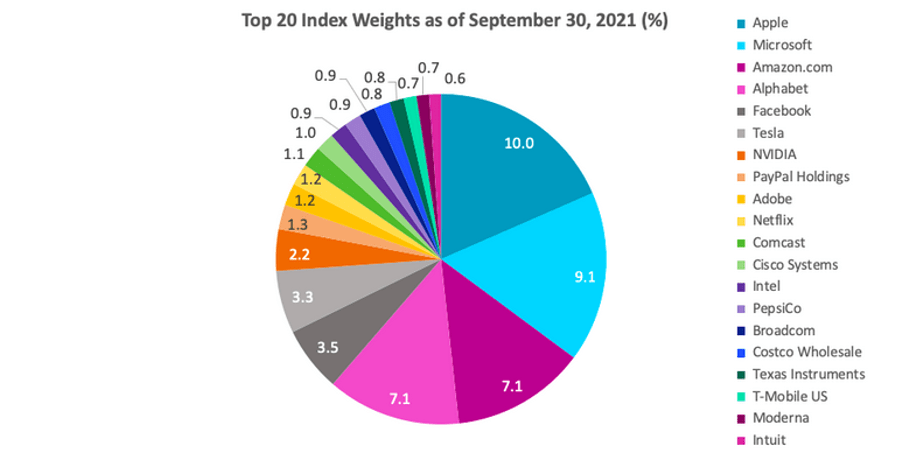

For example, if you invest in an index fund based on the NASDAQ Composite, that means you’re investing in the following:

So if and when you sell off your shares of that index, you’re actually selling pieces of twenty different companies. But notice: Apple, Microsoft, Amazon and Alphabet have the largest pieces by far. Now multiply this dynamic across millions of investors, trading in thousands of similarly weighted funds…

Turns out it doesn’t take a whole lot for those mega-cap stocks to whipsaw all over the place. And when they do, they drag all kinds of other equities around with them, sending huge ripples across the entire market.

So – is this The Big One??

Before I answer that question, let me remind you of the very recent past:

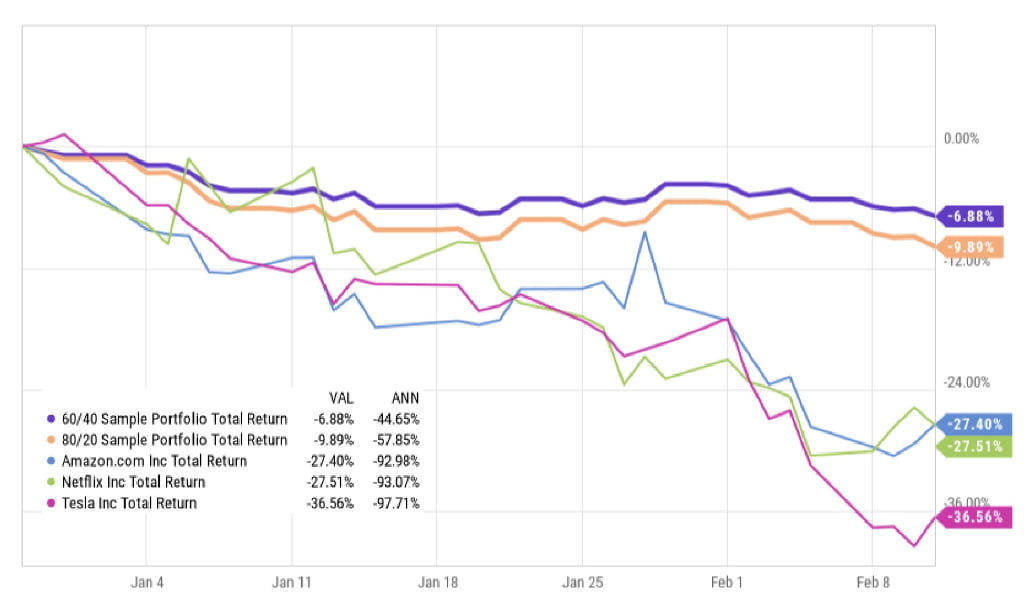

- Early 2016

- Amazon, Netflix, & Tesla each lose about 1/3 their total value.

- A $1M portfolio with 80% stocks and 20% bonds loses $98,900 in just 5 weeks

- Q4 of 2018

- The Fed has just hiked interest rates four times.

- Growth stocks cool off; Mega Cap stocks dive 20% +

- A $1M portfolio with 60% stocks & 40% bonds loses $105,800

In conclusion, this is probably not “the” big one… but it is another pretty big one.

Furthermore, this week’s price action is mostly not a response to something that has happened, but an anticipation for what might happen in the future. With the exception of higher interest rates, the fundamentals look largely unchanged.

— Graham